As confirmed cases of African swine fever (ASF) in the Dominican Republic have led the US Department of Agriculture (USDA) to suspend shipments of all live swine and swine byproducts from Puerto Rico and the US Virgin Islands to the mainland United States, it’s clear industry preparedness for an outbreak is crucial.

That necessity for preparedness is the message KatieRose McCullough, director of regulatory and scientific affairs for the North American Meat Institute (NAMI), presented in a recent webinar. After all, such outbreaks seriously limit live animal and animal product movement in addition to halting exports.

Communication is key

McCullough said the first step in this preparation is for the industry to develop relationships with state animal health officials, and that concept is also echoed by state officials.

“Trading business cards at the time an outbreak starts is too late,” said Dr. Justin Smith, DVM, state animal health commissioner for Kansas. “You’ve got to have those relationships built. If state animal officials aren’t reaching out to you, reach out to them yourselves.”

Smith said in the event of an outbreak, there is a level of continuity of business and operations that still needs to be maintained as the goal will be for animals to still move about in a manner that allows for relatively negligible risk. The key, he said, is how to accomplish this while still isolating the infected animals and plants and keeping the smaller operations in business.

Overall, Dr. Jeff Kaisand, DVM, state veterinarian for Iowa, said discussion needs to center on what happens if a plant or farm becomes infected or in a control area and for the industry to understand what regulatory actions will likely take place.

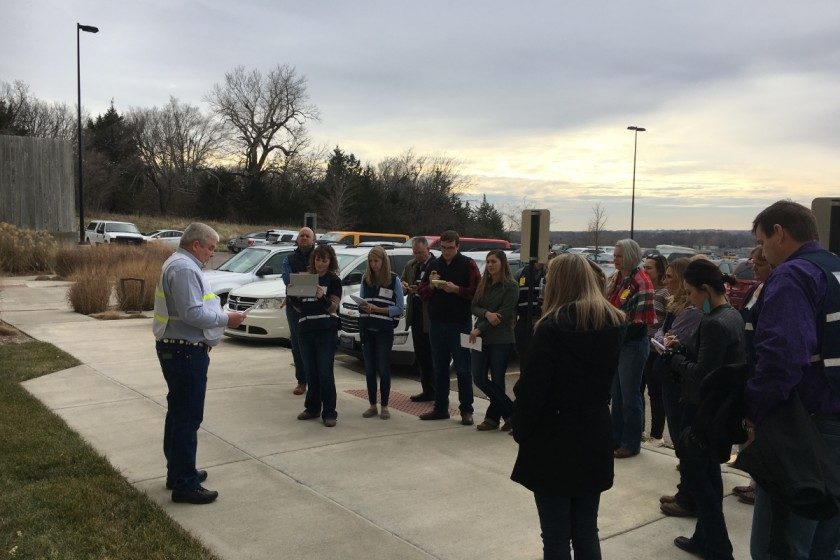

Smith said the Kansas Department of Agriculture conducts a foot-and-mouth disease outbreak exercise each December to help engage the industry and to establish what a response to such an event might look like. He said the event is a bit different every year, but they address issues such as how responders will be dispatched, what their euthanasia team will look like, what large-scale carcass disposal will look like, and the details of their vaccination plans. They also practice how they are going to stop movement of animals and what border checkpoints will look like.

Other exercises have included emergency movement permitting, and some of these permitting drills have included how to move feedlot cattle in a control zone to a packing plant. Participation in exercises and drills allows the agency to gain insight into how the disease response measures could impact operations at a packing plant as well as provide the plants an understanding of what will be expected during a high-impact disease event, Smith said.

To complete such exercises, they have policy, operations, communications, and industry alliance groups participate in addition to collaborating with representatives from several other states. This collaboration between states is also essential as operations don’t happen exclusively within a state as most plants have a presence in multiple states.

“Operations aren’t state-specific,” Smith said. “They do cover a region. We need to build that conversation between the states and have some consistency in response.”

To accomplish this, he said they have worked on permitting drills with their four neighboring states in addition to Texas, and his department is also participating in a large exercise with 12 southern states.

“That regional approach is something we have to continue to expand on,” Smith said.

Focus on biosecurity

Kaisand said he and his department have visited plants recently and encouraged them to develop biosecurity plans now to help minimize or decrease the chances disease will spread.

“Have a plan in place ahead of an outbreak,” Kaisand said. “Implementing biosecurity when an outbreak happens might be too late.”

He said having these plans proved to be essential when his state experienced an outbreak of bird flu in 2015.

According to the Animal Disease Biosecurity Coordinated Agricultural Project (ADBCAP), included in such plans are farm identification information, contact information for an appointed biosecurity coordinator, standards of employee hiring and training, sanitation, traffic control and animal movement details, and plans for the managing of new animal arrivals as well as sick animals.

Obtaining a Premises Identification Number (PIN) from the state animal health official is a key component of these plans, McCullough said. This PIN is a seven-digit alpha-numeric number used by the state and the Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (APHIS) to assist in disease traceability. It is associated with a 911 physical address in addition to a set of matching coordinates that indicates the locations of the animals on a premises. Every production unit, slaughter establishment, livestock market, or assembly yard should have a PIN, she said. Additionally, she said the goal is to help state officials make decisions about whether animals can move and having a PIN would be required for both the premises of origin and the destination for animal movement to occur.

The ADBCAP said public communication is another component of the plans, and there should be an appointed spokesperson for each establishment trained with key messages. Developing a plan for updating the company website with appropriate information for the media and public is also necessary. To this end, some of the exercises Smith and the Kansas officials have conducted include simulated press conferences.

Much effort needs to go into proper planning, but Kaisand suggested the industry needs to also be prepared to improvise and adapt in the event of an outbreak.

“There is no way to totally simulate a disease outbreak,” Kaisand said. “There are pressures, people’s reactions, things going on – you can’t simulate that.”

Nevertheless, taking the effort to make such plans and get everyone in the mindset of responsiveness yields benefits.

“One of the things we always find is the plan might get thrown out the window on the first day because we can’t predict everything,” Kaisand said. “What is priceless is the planning process.”

Boosting ASF preparedness

Industry and regulatory officials agree that widespread use of electronic record keeping programs like AgView will be essential to aiding in response to any foreign animal disease outbreak that might occur in the future. That’s one key takeaway of a recent African swine fever tabletop mock exercise sponsored by the Veterinary Services National Training and Exercise Program.

The event, which took place on Sept. 29 in Iowa, engaged both the industry as well as federal and state officials in efforts to simulate an outbreak and coordinate response plans.

Participants included representatives from the US Department of Agriculture’s Animal and Plant Health Inspection Service (USDA APHIS) VS District 2, the VS Swine Health Center, the USDA National Preparedness & Incident Coordination, the Iowa Department of Agriculture and Land Stewardship, the Food Safety and Inspection Service, Iowa State University, the North American Meat Institute, the National Pork Board, Tyson Foods and Darling Ingredients.

Patrick Webb, DVM, director of swine health programs with the National Pork Board, said the participants in the program learned the goal of using programs like AgView is to shorten the response times from state animal health officials in the event of an outbreak by establishing standardized electronic records from across the industry into one location. After all, Barbara Masters, DVM, vice president of regulatory policy, food, and agriculture with Tyson Foods, said their records have traditionally been paper, and this would require more time for state animal health officials to process in the event of an outbreak.

Rosemary Sifford, DVM, deputy administrator of USDA APHIS, said the overall goals of the mock outbreak exercise were to have training with stakeholders and emergency responders and to identify if current preparedness plans have any gaps. Additionally, improving response capabilities was highlighted as a priority for attendees.